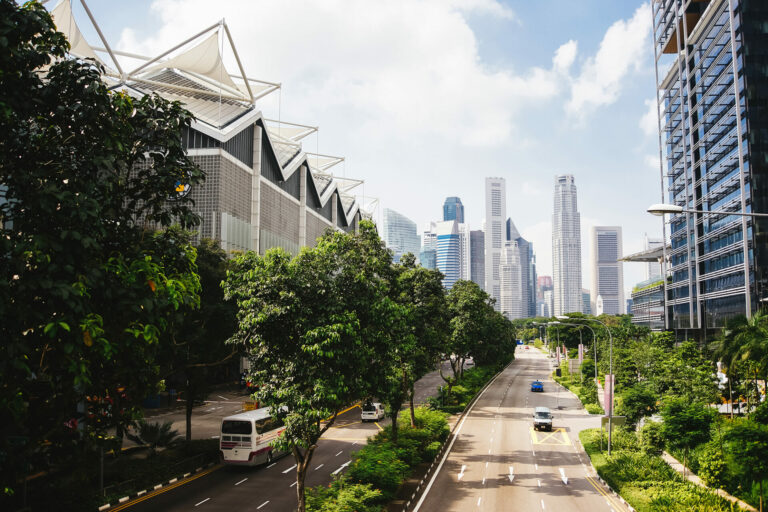

While much has been spoken and written about the U.S. Infrastructure Bill in recent years, neighboring Canada does not receive the same level of global attention. Despite this, the country is in a similar position as it tries to come to terms with creaking infrastructure and a need for investment. According to the latest data, the country has a higher GDP rate per capita than most high-income countries. However, this same data which was collated by Infrastructure Canada shows that both its spending and quality of infrastructure are marginally lower than the average for the same high-income countries. While the differences may be slight, it points to a trend of under- or poor-investment across the infrastructure sector. When we look at the spending itself, the breakdown in figures provides an increasingly complex picture.

Two thirds of Canada’s infrastructure funding go into Social Infrastructure. Further investigation shows that within this budget, 70% is spent on public buildings and health facilities. Education receives 19% while only 8% is spent on housing. While there may be some difficulty in comparing funding amounts with such blunt metrics, it is interesting to look deeper into spending on transport. While the sector only receives 11% of the overall spending, the budget spent on roads only accounts for a fraction of this.

So where does this all leave the Canadian infrastructure landscape? Unfortunately, quantifiable data is hard to come by and significantly, it takes years to collect. The last released report on the sector was assembled by a group of federal bodies, associations and networks in 2019. The 2019 Canadian Infrastructure Report Card was a collective effort that followed on from similar report cards in 2016 and 2012. According to the group, the reports showed that all is not well within the sector. “[It is] a timely update on the state of Canada’s public infrastructure across all core public infrastructure asset categories: roads and bridges; culture, recreation, and sports facilities; potable water; wastewater; stormwater; public transit; and solid waste. It finds that the state of our infrastructure is at risk, which should be cause for concern for all Canadians. In order to change course, Canada’s public infrastructure will require significant attention in the coming decades.”

In fact, the report is even more critical. It showed an infrastructure network that was aging, in poor condition and struggling to meet the needs of Canadians. As far back as 2019, the statistics showed a worrying trend:

Nearly 40 percent of roads and bridges were in fair, poor or very poor condition, with roughly 80 percent being more than 20 years old. Between 30 and 35 percent of recreational and cultural facilities were in fair, poor or very poor condition. In some categories (such as pools, libraries, and community centers), more than 60 percent were at least 20 years old. 30 percent of water infrastructure (such as watermains and sewers) were in fair, poor or very poor condition.

“In order to change course, Canada’s public infrastructure will require significant attention in the coming decades.”

Five years on from the report, we are yet to be given an update. What is fair to say, however, is that infrastructure is a sector that is constantly in flux. Repairs and new construction is taking place all the time, so it could be disingenuous to paint an overly negative picture. However, the overall view is of an infrastructure network that is being underfunded and is, as a result, incrementally worsening. The report itself was critical of a number of infrastructure aspects. “A concerning amount of municipal infrastructure is in poor or very poor condition. Infrastructure in this condition represents an immediate need for action, as the rehabilitation or replacement of these assets is required in the next 5-10 years to ensure that the services it provides continue to meet the community’s expectations. An even larger proportion of municipal infrastructure is in fair condition. Infrastructure in this condition represents a view of things to come in the medium to long term. This infrastructure will continue to deteriorate over the next decade, falling into poor and very poor condition if rehabilitation or replacement actions are not taken.”

At the time, a pre-COVID world, this was an ominous view in itself. For Bill Karsten, President of the Federation of Canadian Municipalities, it was time to take action. “We’re talking about roads, bridges, libraries, arenas and more—things Canadians rely on every day. Good, reliable infrastructure supports our quality of life in communities across the country, so Canadians should find these results concerning.”

So, what has been done since then to revitalize Canadian infrastructure? The picture is unclear. Certain measures have been introduced but without quality data to back it up, we are left in the dark. Prior to the report, in 2016, the Investing in Canada plan was announced. This was a federal commitment of over $180 billion over a twelve-year period. So far, figures show that it has invested $147 billion of this in over 95,000 projects. It is currently unclear what impact this investment will have on the next Report Card, but it is hoped that there will be a positive swing across all metrics.

Another recent announcement could also herald a new dawn for infrastructure projects, particularly those in indigenous areas. Last month, Canada Infrastructure Bank (CIB) announced a $100 million loan participation agreement with the First Nations Bank of Canada (FNBC). This program will support the affordable financing and accessing of funding for infrastructure projects in First Nations, Métis, and Inuit communities. This funding, it is hoped, will ensure an improvement in living conditions, new economic opportunities, and housing. According to Ehren Cory, CEO of Canada Infrastructure Bank, the funding is vital to improving the lives of Canadians. “Through this investment, Indigenous communities will work with FNBC to access critical financing to develop much-needed infrastructure in their communities and advance socio-economic reconciliation.”

The long-term outcomes of this fund, alongside the Investing in Canada plan, are currently unknown. It is certainly encouraging to see long term projects such as Metrolinx and the Toronto Waterfront Revitalization Initiative come to fruition, but without evidence, much of this is guesswork. With no news on the horizon as to the completion of the next Report Card, we cannot be sure. Good things are happening, that is clear, but are they good enough to stem the tide? We will have to wait and see.